Anything that is alive is in a continual state of change and movement. - Robert Greene

We know a language is alive when it is constantly changing. It doesn’t take a scholar to realize that the English of Shakespeare’s time was quite different to contemporary English. Even during the Shakespearean era of English, there were people who complained about all the new words he coined, claiming that the poet was contributing to the degradation of the English language. Most famously, Thomas Sprat, a Bishop in the 1600s, once asked the Royal Court if they could go back to the times of “primitive purity” when things were short and to the point, preferring the language of countrymen over that of “wits and scholars”.1 So if you’ve ever used the phrase “in a pickle”, which Shakespeare coined, just know that Thomas Sprat was turning in his grave.

Sprat’s resistance to language change was and is not uncommon. In fact, my 10th grade English teacher held quite purist views about language herself. I distinctly remember a time where she would dock marks on any creative writing assignment or essay that used the word ‘towards’, stating that the only correct form was ‘toward’. Adding the -s at the end was simply unacceptable. This was only one example of all the highly specific grammar rules she had us follow that didn’t really hold much water in hindsight.

I can imagine those that hold these views must self-implode every time they open Twitter, as the English language continues to evolve at a faster rate than ever before. This is thanks in large part to the internet and how easy it has become to communicate with those outside our regular circles. As words like ‘doomscrolling’ and ‘fitspo’, both originating from distinctly online phenomena, are used more and more, there comes with it an adverse reaction from the more conservative boomers and self-proclaimed “grammar police”.

Now in typical scholarly fashion, let’s look at both sides of the argument. Is language degradation a real thing and should we be concerned with it?

Are we dumbing down the English language?

In the 2006 film Idiocracy, Private Joe Bauers (played by Luke Wilson) wakes up in the future after being part of a hibernation science experiment. The film itself is a social satire of a world destroyed by mass commercialization and overconsumption, overrun by idiots who seem addicted to a green energy drink called “Brawndo”. An interesting aspect of the film is how the idiots speak compared to Bauers who is the only “smart” person left alive.

We can see the link made between intellect and language, the idea that English is something that can be dumbed down, whether it is a consequence or the cause of society’s downfall. Even more troubling, however, is the fact that the types of English used by the idiots in the film do exist in reality and are spoken mostly by minority groups. The narrator at the beginning of the movie states that our protagonist has trouble communicating with the idiots because by then the English language had “deteriorated into a hybrid of hillbilly, valley girl, inner city slang, and various grunts”. While “hillbilly” is a type of English associated with a lower class of the rural American south, “valley girl” has its own negative connotations as a type of English spoken by airy yet affluent women who are overly concerned with social status. The use of “inner city slang”, however, directly relates to race as well as class as it is most commonly associated with poor black neighbourhoods in big cities. A few examples of this in the film are highlighted below:

- “I got too many damn kids, I thought you was on the pill or some shit” → Verb agreements such as “you was”, “we was”, “they was” is common in AAVE (African American Vernacular English) and here is used by one of the first idiots we see in the film.

- “So you smart, huh?” → The omission of the copula ‘are’ is a feature of AAVE.

- “I’ve never seen no plants grow out of no toilet.” → Another feature of AAVE is the use of double negatives.

The thing about AAVE is that it is an incredibly structured dialect of English that faces stigma for its roots in black communities.2 A lot of criticism surrounding it cannot be distanced from racism itself as other dialects of English such as California English do not come under as much fire and, in fact, surf-speak such as calling people “brah” and saying you’re “totally stoked” is often embraced in popular culture.

Throughout history, languages have always branched off into dialects and local varieties. That is how from Latin, a multitude of languages were born: French, Italian, Spanish, and more, which in turn branched off into various dialects and so on. English has never been a static language either, for example the word for a constant complainer in Old English was “gnashnab” which fell out of use despite there being no shortage in complaining.

The point of all of this is to say that language has always been evolving and will continue to evolve. And as words fall out of favour for new ones, we adapt and learn them to suit our needs. In celebration of this, the following section will discuss one of my favourite words gifted to us by the internet.

SPAM SPAM SPAM

If you don’t know what Spam is there are, at the current time of writing, two definitions:

- a canned meat product made mainly from ham.

- irrelevant or inappropriate messages sent on the internet to a large number of recipients.

The second definition did not come into existence until the 1980’s but to understand its roots more clearly, we have to go decades back to World War II, when soldiers were forced to eat cans of non-perishable meat for sustenance.

Spam became such a staple part of American soldier’s diets that they eventually became so sick of it. In fact, it even became common practice to send hate mail to the son of the company’s founder.3 If you think that’s where the second definition of ‘spam’ originated from however, you would be wrong.

The inescapability of Spam in all aspects of life eventually resulted in a Monty Python sketch that aired in the 70’s wherein two unknowing patrons are dropped into a cafe, soon to find out that every menu item seems to contain Spam. It was a popular sketch amongst computer programmers for reasons still unknown today and when a program was invented to flood someone’s server with meaningless data, the nerds began to refer to it as sending ‘spam’.4

It wouldn’t be long before this definition of the word caught on to the general public, before being officially added to the New Oxford Dictionary of English in 1998.5

Anyone who speaks English generally knows what ‘spamming’ means. Most people have likely complained, or been gnashnabs, about receiving spam calls or emails. It is a phrase that has nested itself into our general lexicon despite being a relatively new word in the history of the English language. Even a linguistic purist who sticks their nose up at newer language trends has likely adopted the second definition into common usage as well.

In defense of gatekeeping.

Change can be scary, we can all empathize with this fear. While we may be able to see the beauty in language change, it won’t alter the fact that someday you might feel outcast for not speaking like certain members of a group, much like Private Joe Bauers felt with the idiots. But this is a function of language and society that has always existed, which linguists refer to as “communities of practice”.6 To take a biblical example, in the Book of Judges, two opposing Semitic tribes–the Gileadites and the Ephraimites–were at war. As the infamous story goes, The Gileadites had set up a blockade at the Jordan River, capturing any Ephraimites trying to get back to their land. The only issue was that the Ephraimites did not look so different from the Gileadites and spoke the same language as well, the main difference being that they could not pronounce the sh-sound as it did not exist in their dialect. In the end, the Gileadites were able to win the battle by simply asking any passing soldier to utter the passcode “Shibboleth”. Those that pronounced it “Sibboleth” were slain on the spot.

Something similar can be seen in Quentin Tarantino’s film, Inglourious Basterds, in which Lt. Archie Hicox (played by Michael Fassbender) is an undercover British spy trying to infiltrate a group of Nazis in an underground tavern. Despite his ability to speak German fluently, albeit with a slight accent, it was one mistake that gave him away, leading to his ultimate demise.

In this scene, Hicox is shown ordering three glasses of scotch while raising three fingers. The Nazi soldier across from him, immediately homes in on this, realizing right away that this man is not German for the sole fact that the German way is to use the thumb, index, and middle finger to communicate the number three. Such a small detail had outed Hicox as a British spy, an outsider who otherwise may have been able to infiltrate with relative ease.

Even in our modern age, pretending to be someone you’re not is incredibly common, although the stakes may not be as high as an ancient war or WWII espionage. Communities of practice are still quite invested in ousting anyone trying to infiltrate their online circles and outrage can be quite high when someone is not who they purported to be. For example, the reality show Catfish, which first aired in 2012, capitalizes on this by investigating whether someone is a ‘catfish’, ie. someone who creates a fake online persona, usually with the intent to trick or scam. In one case that rocked Twitter in 2019, a popular online user with the handle @emoblackthot was revealed to be a cis black man pretending to be a black woman.7 Many felt duped as he received frequent Cash App donations from his followers for speaking about his ‘experience’ as a dark skinned woman, suffering from endometriosis and going as far as to give tips on dealing with menstrual cramps.

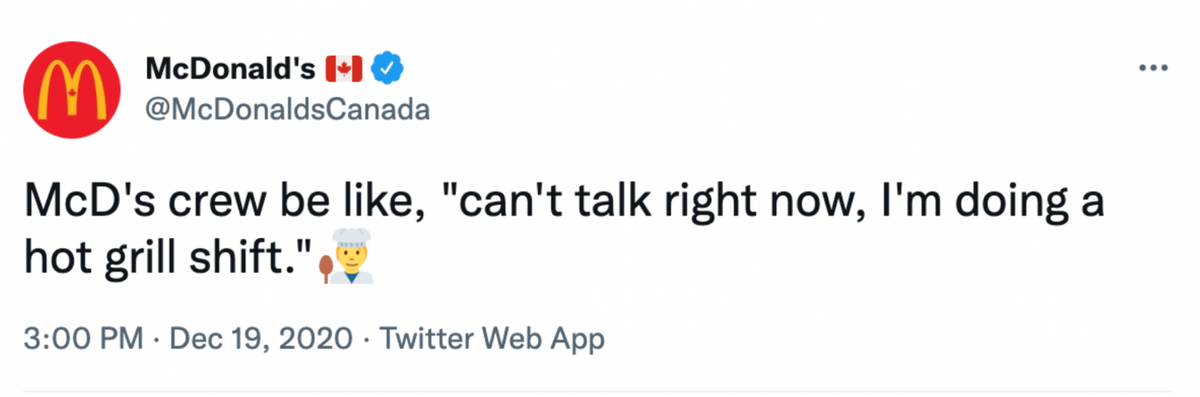

Communities are important and being able to signal community membership can sometimes act as a method of protection. In the age of the internet, anyone can pretend to be anyone else but they’ll find that it’s quite easy to get caught if they’re pretending to be part of a community of practice that isn’t authentically theirs. Corporate brands are getting made fun of for misusing AAVE on an almost daily basis in an effort to appeal to Gen-Z, while an entire Twitter page called aave struggle tweets (@aavenb) exists, dedicated to pointing out incorrect use of AAVE by those trying to build a cool online persona around it.

Being fluent in the language we speak does not mean we will always understand 100% of the words spoken. For example, legal jargon is quite hard for the average person to understand if they’ve never studied law. The same goes for any specialized field, whether it is medicine, philosophy, art, and so on. Rather than let it be a point of contention, why not embrace the infinite amount of possibilities that language offers?

Calamus gladio fortior.

If you’re still worried the English language will be incomprehensible to you within your lifetime because of all the slang words that seem to pop up like a game of whack-a-mole, a great place to keep up-to-date is Merriam-Webster’s “Words We’re Watching” list. These are words that are currently circulating but have not yet been officially added to the dictionary, such as “sus’ and “stonks”, each a derivation of the word “suspicious” and “stocks”, respectively. Recently, the word “laggy” was added which we, as an internet service provider, wouldn’t even wish on our worst enemy.

In conclusion, let the internet be a tool to guide you in unlocking all the cool new words and phrases our language has to offer rather than a place of frustration. And if you ever feel bad about yourself for not picking up on language change fast enough, feel good in the fact that even the trendiest of phrases may one day be looked back on as outdated. However, if you prefer to speak a language that won’t change on you, there’s always Latin as a last resort.

Thank you to David P. and Danilo T. for the constant support and guidance.

- Returning to Primitive “Purity and Shortness” in the Royal Society

- African American Vernacular English (AAVE) Grammar

- Hormel Kept a 'Scurrilous' File of Hate Mail About Spam from World War II GIs

- How Spam (The Mystery Meat) Morphed Into Computer Spam: Marshall's Musings

- Communities of practice: Where language, gender, and power all live

- AAVE struggle tweets

- Words we’re watching

- Why @EmoBlackThot's Identity Reveal Hurt Black Women So Much

- @McDonaldsCanada